“Why the silence?”: Giving a Voice to the Lived Experiences of STEMM Librarians

Amani Magid (she/her)

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5664-9982

Coordinator of Instruction, Associate Academic Librarian for the Sciences and Engineering

NYUAD Library

New York University Abu Dhabi

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

am6087@nyu.edu

Ana Torres (she/her)

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2994-6820

Head of Library Operations

Bern Dibner Library of Science and Technology

New York University

New York, NY

at1387@nyu.edu

Abstract

Inclusion, diversity, belonging, and equity (IDBE) are tenets discussed and developed in many universities and university libraries. Although there were studies on IDBE in libraries in general, the authors of this study were particularly interested in what Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Medicine (STEMM) librarians were facing or not facing regarding IDBE. We were unable to locate any known study focusing on STEMM librarians' lived experiences regarding IDBE. Thus, our study aimed to explore this area further. A survey consisting of multiple-choice, Likert and short-answer questions was sent to STEMM librarians via specific listservs. In this study, we use a grounded theory approach and analyze three of the questions in the survey. This study would particularly interest librarians who would like to ascertain the climate of IDBE and the intersection with social justice in STEMM Librarianship. Also, we provide strategies to improve the climate and provide a more inclusive, diverse, equitable and belonging environment for STEMM Librarians. Our data analysis shows that STEMM librarians who identify as People of Color encounter negative behaviors, experiences, and attitudes at a much higher rate than STEMM librarians who are white. In addition, many STEMM librarians who identify as white report white privilege awareness.

Keywords: Social justice, Academic libraries, Diversity, Lived experience, STEMM librarians

Recommended Citation:

Magid, A., & Torres, A. (2024). “Why the silence?”: Giving a voice to the lived experiences of STEMM librarians . Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship, 105. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl2815

Introduction

Many studies have been conducted on the climate of IDBE for academic librarians. However, this study may be the first one aimed at the climate in which STEMM librarians work. The questions driving this research are, "What are the issues that STEMM librarians are faced with? What are STEMM librarians observing and/or experiencing? Is there a difference in what STEMM librarians are facing due to the different ethnic/racial backgrounds? How can the results of this study be used to ascertain the climate of libraries, particularly for STEMM librarians, especially around the subject of social justice and IDBE? What can be done programmatically or strategically in libraries to improve the experiences and bring social justice to the forefront of libraries' core and everyday experiences?

This paper uses a grounded theory approach. Grounded theory is “...a systematic approach to inquiry with several key strategies for conducting inquiry” (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Charmaz, 2017, 02:21). Grounded theory…“ favors theory construction over description, constructing fresh concepts over applying received theory, theorizing processes over assuming stable structures.” (Charmaz, 2017, 02:38). This systemic methodology was critical, as we wanted to capture STEMM librarians' voices.

This research study is partly informed by the identity of the authors and their lived experiences as women of color in academic libraries. We are a second-generation Sudanese-American and a first-generation Colombian-American in two countries and time zones. Our work was primarily completed asynchronously through Zoom, Google Docs, Trello, and other tools. We both work for libraries under the New York University Division of Libraries. At New York University Division of Libraries, the inaugural Inclusion Diversity Belonging and Equity Committee was instituted in the mid-2010s, and it has since become an integral fabric of the Division of Libraries with regards to collections, resources, and services, and more recently, with regards to recruitment, retention, and advancement (“Inclusion, diversity, belonging, equity, & accessibility (IDBEA)”, n.d.). We began this research project in 2019 and because of the pandemic, there was a delay in analyzing the results.

Literature Review

Recruiting and Retaining Diverse Employees

There are quite a few studies on examples of IDBE, and/or the lack thereof, in academic libraries. Most of these studies are from a North American perspective. Some of the studies focused on recruiting and retaining diverse employees (Chadley, 1992; Chang, 2013; Neely & Peterson, 2007), while another study focused on retaining and advancing middle managers who are People of Color (POC) (Bugg, 2016). There are two case studies, with one focusing on hiring practices and instilling a practice of hiring for diversity at a specific library, and the other is a narrative of an African-American library employee passed up for promotion based on the employee’s ethnicity (Anderson et al., 1990; Andrade & Rivera, 2011). Hathcock (2015) examines how libraries are currently addressing diversity and why it has not been attained optimally, and provides alternative solutions. Vinopal (2016) also examines diversity in library employees and offers suggestions for library leaders. Some suggestions offered by Vinopal include: having open conversations with employees about implicit bias and to implement strategies to remedy and/or avoid it, to include words such as “anti-racism” “whiteness” and other similar terms in a library plan instead of only including “diversity” and “inclusion,” in an effort to name the problem. Riley-Reid (2017) explores how to retain academic librarians of color. Diversity residency librarians and the idea of such positions as a means of multiculturalism in academic librarians is questioned by Linares and Cunningham (2018) by exploring narratives of librarians who identify as women of color.

Diversity in Library and Information Science Programs

One of the seminal works about diversity is the edited volume, Knowledge Justice: Disrupting Library and Information Studies through Critical Race Theory, which uses Critical Race Theory as a framework to assess the Library and Information Science field (Leung & López-McKnight, 2021). The chapter “Leaning On Our Labor” takes a critical look at diversity in libraries and how diversity can be commodified by ignoring whiteness and also by establishing diversity residency programs which temporarily give the appearance of a diverse library staffing (Brown et al., 2021; Leung & López-McKnight, 2021).

Diversity Initiatives

How libraries initiated and continued diversity initiatives are relevant to this research. Before discussing diversity in the library workplace, we recognize the diversity in Library and Information Science (LIS) programs as stepping stones (Kim & Sin, 2008; Love, 2010; Wheeler & Hanson, 1995). At least one study argues that diversity efforts to recruit and retain will improve once there is a concentration on increasing faculty diversity in LIS programs (Jaeger & Franklin, 2007). Stanley (2007) conducted focus groups with undergraduate students to ascertain their knowledge about librarianship as a career and found that many were not exposed to thinking about a career in librarianship.

Some studies focus on the perceptions of minoritized groups on various IDBE topics. The newest of these at the time of writing is the study by Caragher and Bryant (2023) which concentrates on employees who identify as Black and non-Black and how they perceive hiring, retaining and promoting minoritized employees. Alabi's (2015) study focuses on different types of microaggressions experienced by librarians of all ethnic/racial backgrounds. Swanson, Tanaka, and Gonzalez-Smith (2018) conducted a qualitative study to ascertain the lived experiences of academic librarians of color.

Social Justice

The topic of social justice within librarianship is a growing field. Social Justice is the idea that “… societies can eliminate the systems and barriers that create unearned privilege and marginalization while upholding human rights” (Colón-Aguirre & Cooke, 2022; Cooke et al., 2016, p. 108). The newest scholarship in this field is a book edited by Brissett and Moronta (2022) with contributing authors who include various strategies for making social justice a normalized part of the field of librarianship, from using LibGuides to overcoming diversity fatigue. The only scholarship we were able to locate on social justice and STEMM librarianship is a four-part series, Science Librarianship and Social Justice, which reviews concepts in inclusion, diversity, and equity and provides examples of how this might show up within STEMM librarianship (Bussmann et al., 2020a, 2020b, 2021, 2022).

Vocational Awe

We would be remiss not to include the landmark article on vocational awe in librarianship by Ettarh (2018). This scholarly work espouses that due to the awe of the vocation, librarians believe that the vocation can never do harm and that those who work in libraries are of almost “religious goodness.” This viewpoint is highly subjective and unrealistic, stemming from a place of privilege held by individuals within the profession. Historically, the library profession has been dominated by women who identify as white, and therefore many of the beliefs of “religiousness” within librarianship come from this historical and social perspective. Unfortunately, this belief may lead to disparities in the workplace for those who are not of the majority population (North American view), and disparities in the services provided.

Methods

Survey: Data Collection

We built and distributed a survey with STEMM librarians in mind. Using the survey from Swanson's study as a model, we constructed a Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com) survey (Swanson et al., 2018; Torres & Magid, 2023). The survey consisted of 10 multiple-choice questions, five open-ended questions, 20 Likert scale questions for all participants, and five Likert scale questions solely for participants who identified as Librarians of Color. The survey received ethical approval from the New York University Institutional Review Board. After several test runs, we determined that it would take a participant approximately 15 minutes to complete the survey. We distributed the survey on listservs sponsored by the Engineering Libraries Division of the American Society for Engineering Education, the Science Technology Section of the Association of College and Research Libraries, Medlibs from the Medical Library Association, and the Physics-Astronomy-Mathematics Division of the Special Libraries Association. We safeguarded participants' identities by:

- Incorporating multiple-choice and Likert scale questions

- Activating anonymization settings in Qualtrics

- Stripping any identifying data from the open-ended responses

- Merging identity data for reporting purposes

As an incentive, we offered participants who completed the survey a chance to enter a raffle for small financial compensation. We did not collect any identifying information and participants could skip questions or withdraw at any point. The survey was sent to the listservs the first week in June 2019 and remained open for 30 days.

The Focus of the Study: Ethnic/Racial Identity, Experiences and Witnessing

We aimed to identify experiences related to ethnic or racial identity shared by STEMM librarians based solely on participants' self-reporting and not considering any known theories or hypotheses around racial and ethnic identity. We narrowed the analysis to three questions:

- How do you describe your ethnic/racial identity? - Question 2 (Q2), a multiple-selection question

- Please describe any situations related to your ethnic/racial identity you have experienced at work within the last month - Question 32 (Q32), an open-ended question

- Please describe any situations you have witnessed related to ethnic/racial identity of colleagues at work within the last month - Question 35 (Q35), an open-ended question

Additionally, we applied a constructivist grounded theory approach in analyzing the open-ended questions and a mixed-method approach in examining relationships between all variables. We performed all analyses on MaxQDA 2022 (VERBI Software, 2022), a qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research tool.

Multiple-Selection Question: Ethnic/Racial Question 2

We instructed the participants to select as many ethnic/racial identities as they identified with, or to self-report.

When we constructed the survey, we intended to report on each ethnic/racial identity, especially for those who preferred to self-describe. Though we felt it imperative to report with high granularity, we had to consider that the numbers for each ethnic/racial identity were small and 1) this could compromise a participant's identity, and 2) it would be difficult to extrapolate information when comparing each of the smaller ethnic/racial groups against the larger group who identified as white. Hence, we merged groups as follows:

- People of Color - participants who selected one or more ethnic/racial identities, where at least one of the ethnicities is a recognized minoritized population in North American society, from the multiple-selection list and all participants who self-described.

- Prefer not to answer - no merging needed.

- White - participants who solely identified as white - no merging needed.

Constructivist Grounded Theory Approach Questions 32 and 35

As STEMM librarians from diverse backgrounds, we approached Q32 and Q35 with a constructivist lens. Based on this subjective approach, we adapted grounded theory analysis by incorporating open, axial, and selective coding. As a first step, we carried out open coding. We independently looked at all the responses for Q32 and Q35 and assigned codes and subthemes to phrases. A response could be coded several times (Figure 1). This step was followed by axial coding. In axial coding, we came together and discussed each code in context, drafted definitions, and formed connections among the SUBTHEMES that would emerge as THEMES. We recorded the themes, subthemes, and definitions in a codebook (Torres & Magid, 2023). We replaced the drafted definitions with definitions from authoritative resources. Selective coding followed. Following this iterative process, we scrutinized the data, re-combined, and re-defined overarching themes.

Mixed-Methods: Cross-Tabulations Ethnic/Racial Identities and Themes

We concluded our analysis with a mixed-methods approach using cross-tabulation to find relationships within the data. We examined two variables: ethnic/racial categories as reported in Q2 and the theme structure.

Results and Discussion

Survey: Data Collection and Ethnic/Racial Identity

Two hundred and nine participants completed the survey. We removed eight participants as they left all survey questions blank. In total, we received responses from 201 participants. Of the 201 participants, 67 (N=67, Table 1) responded to Q32 and 44 (N=44, Table 2) responded to Q35.

When selecting ethnic/racial identities, 69% of the participants (N=67) (Table 1) who answered Q32 and 73% of the participants (N=44) (Table 2) who answered Q35 identified as white. Though these percentages were very close, they were less than 86.7% reported on the 2017 ALA Demographic Study, a report we benchmarked against (Rosa & Henke, 2017). The small number of participants is one probable cause for the difference. Still, these large percentages indicate the disparity in ethnic/racial representation in STEMM librarianship. Caragher and Bryant (2023) reported a similar finding in their study. They noted that the large percentage of librarians identifying as white “...points to the underrepresentation of racialized groups in the field of librarianship” (p. 146).

| Reported Ethnic/Racial Identities for Question #32 | ||

| Ethnic/Racial Identity | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| People of Color | 20 | 30% |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 1% |

| White | 46 | 69% |

| Total | 67 | 100% |

| Reported Ethnic/Racial Identities for Question #35 | ||

| Ethnic/Racial Identity | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| People of Color | 11 | 25% |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 | 2% |

| White | 32 | 73% |

| Total | 44 | 100% |

| Q32 THEMES | # of occurrences |

|---|---|

| IDBE IN THE WORKPLACE (IDBE) | 6 |

| diversity hiring | 2 |

| opportunities for professional development | 2 |

| workplace cliques | 2 |

| Negative behavior, experiences and/or attitudes (NBEA) | 26 |

| anti-racism | 1 |

| antisemitism | 1 |

| challenging authority | 1 |

| challenging colleagues of color | 2 |

| cultural representation | 2 |

| discrimination | 1 |

| gender disparity | 1 |

| IDBE hypocrisy | 1 |

| institutional racism | 1 |

| internalized unawareness | 1 |

| lack of management support | 2 |

| man’s world | 1 |

| marginalization | 1 |

| microaggression | 5 |

| minority tax | 1 |

| passing_worries | 1 |

| protests | 1 |

| racism | 1 |

| social categorization | 1 |

| Positive behavior, experiences and/or attitudes (PBEA) | 12 |

| camaraderie | 2 |

| ensure diversity | 1 |

| equity | 2 |

| equity training | 2 |

| speaking up for | 5 |

| WHITENESS (W) | 25 |

| predominantly white workforce | 2 |

| white fragility | 3 |

| white privilege, awareness of | 13 |

| white-peating | 1 |

| whiteness and masculinity | 6 |

| NO RESPONSE (NR) | 30 |

| more information needed | 2 |

| none | 27 |

| prefer not to say | 1 |

| Q35 THEMES | # of occurrences |

|---|---|

| IDBE IN THE WORKPLACE (IDBE) | 2 |

| diversity hiring | 2 |

| token hire | 1 |

| Negative behavior, experiences and/or attitudes (NBEA) | 20 |

| behavioral _rude | 1 |

| colorism | 1 |

| confrontation | 2 |

| discrimination | 2 |

| IDBE hypocrisy | 1 |

| isolation | 1 |

| marginalization | 1 |

| microaggression | 2 |

| obstacles to advancements | 1 |

| passing_worries | 1 |

| retention failure | 1 |

| internalized unawareness | 4 |

| unawareness_statement | 2 |

| Positive behavior, experiences and/or attitudes (PBEA) | 9 |

| allies | 1 |

| camaraderie | 1 |

| ensure diversity | 1 |

| laudatory | 1 |

| mutual respect | 1 |

| witnessing IDBE | 4 |

| WHITENESS (W) | 5 |

| predominantly white workforce | 2 |

| white fragility | 1 |

| white privilege, awareness of | 2 |

| NO RESPONSE (NR) | 19 |

| none | 19 |

For Q32, we identified 36 subthemes and for Q35, we identified 25 subthemes (Table 3 and Table 4). Some subthemes appeared in both questions, but some were unique to each question. We grouped subthemes into themes. Frequencies for subthemes under a theme were aggregated and elevated to the theme level. In grouping subthemes for Q32 and Q35, we identified two frequently occurring topics, “IDBE in the Workplace” and “Whiteness.” (defined below) We also discovered that participants described their experiences using positive and negative language, leaving questions blank or writing in “none” or “prefer not to answer.” With this in mind, we recognized five themes in Q32 and Q35.

- Inclusion, Diversity, Belonging, and Equity (IDBE) in the Workplace - references to Inclusion, Diversity, Belonging, and Equity and how this translates to the work environment.

- Negative Behavior, Experiences, and/or Attitude (NBEA) - elements of human behavior, experiences, and/or attitudes that an individual finds unpleasant, depressing, or harmful.

- Positive Behavior, Experiences, and/or Attitude (PBEA) - elements of human behavior, experiences, and/or attitudes that an individual finds meaningful, rewarding or emotionally appealing.

- Whiteness (W) - the result of a social or cultural process that situates white people in a place of power and privilege because of their skin color and white racial identity. We coded for whiteness when a participant wrote the word "whiteness" in their response.

- No response (NR) - when a participant left the question blank or wrote "none" or "prefer not to answer. (NR).

Themes and Subthemes in Q32 (Please describe any situations related to your ethnic/racial identity you have experienced at work within the last month)

When reviewing the results for Q32, there were three subthemes under IDBE, 19 under NBEA, five under PBEA, five under W, and three under NR. NBEA has the highest number of subthemes, almost three times more than PBEA. The themes in order of occurrence from highest to lowest were NR (30 times), NBEA (26 times), W (25 times), PBEA (12 times), and IDBE in the Workplace (six times). NBEA was coded a little more than twice as many times as PBEA. Subthemes that appeared five or more times were “none” under NR, “microaggressions” under NBEA, “speaking up for” under PBEA, and “white privilege, awareness of” under W.

Themes and Subthemes present in Q35: Please, describe any situations you have witnessed related to ethnic/racial identity of colleagues at work within the last month

When reviewing the results for Q35, there were two subthemes under IDBE, 13 subthemes under NBEA, six subthemes under PBEA, three subthemes under W, and one subtheme under NR. The themes in order of occurrence from highest to lowest were NBEA (20 times), NR (19 times), PBEA (nine times), W (five times), and IDBE in the Workplace (two times).

Subthemes that appeared four or more times were “none” under NR, “internalized unawareness” under NBEA, and “witnessing IDBE” under PBEA.

| People of Color | Prefer not to answer | White | Total | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDBE in the Workplace (IDBE) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 6% |

| diversity hiring | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| opportunities for professional development | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| workplace cliques | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Negative behavior, experiences and/or attitudes (NBEA) | 18 | 0 | 8 | 26 | 26% |

| anti-racism | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| antisemitism | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| challenging authority | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| challenging colleagues of color | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| cultural representation | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| discrimination | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| gender disparity | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| IDBE hypocrisy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| institutional racism | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| internalize unawareness | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| lack of management support | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| man's world | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| marginalization | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| microaggression | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| minority tax | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| passing_worries | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| protests | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| racism | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| social categorization | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Positive behavior, experiences and/or attitudes (PBEA) | 6 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 12% |

| camaraderie | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| ensure diversity | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| equity | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| equity training | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| speak up for | 3 | 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| Whiteness (W) | 2 | 0 | 23 | 25 | 25% |

| predominantly white workforce | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| white fragility | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| white privilege, awareness of | 0 | 0 | 13 | 13 | |

| white-peating | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| whiteness and masculinity | 1 | 0 | 5 | 6 | |

| No Response (NR) | 7 | 1 | 22 | 30 | 30% |

| more information needed | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| none | 6 | 1 | 20 | 27 | |

| prefer not to say | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| TOTAL | 36 | 1 | 62 | 99 | 100% |

Some subthemes were only coded twice. For our study, from this point forward, we chose to discuss those subthemes we coded at least three or more times. The fact that we did not discuss all of these does not take away from their importance to the overall climate of social justice in STEMM librarianship. We want to recognize that all these subthemes in our study can hinder or advance the development of a fair, just and equitable climate for STEMM librarianship.

Of the five themes, IDBE appeared the least (6 times). The subthemes “diversity hiring,” “opportunities for professional development,” and “workplace cliques” were mentioned equally across the categories for participants who are People of Color and white.

NR appeared the most, but no additional information was obtained from these responses. NBEA followed, appearing 26 times. Participants who identified as People of Color mentioned NBEA 18 times, and participants who identified as white mentioned NBEA eight times. Looking at the subthemes, participants who identified as white mentioned “IDBE hypocrisy,” “discrimination,” “internalized unawareness,” “man's world,” and “protests.” Those from the category People of Color mentioned “anti-racism,” “antisemitism,” “challenging authority,” “cultural representation,” “gender disparity,” “institutional racism,” “lack of management support,” “marginalization,” “minority tax,” “passing_worries,” “racism,” and “social categorization.” Both groups mentioned “challenging colleagues of color” and “microaggression.”

PBEA appeared 12 times. Participants who identified as People of Color mentioned PBEA six times, as did participants who identified as white. Looking at the subthemes, participants who identified as white mentioned “ensure diversity” and “equity training.” Those from the category People of Color mentioned “camaraderie.” Both groups mentioned “speak up for” and “equity.”

Whiteness appeared 25 times. Participants who identified as People of Color mentioned “whiteness” two times, but those who identified as white mentioned “whiteness” 23 times. Looking at the subthemes, participants who identified as white mentioned “predominately white workforce,” “white privilege, awareness of,” and “white-peating.” Both groups mentioned “white fragility” and “whiteness and masculinity.” Of the three subthemes, “white privilege, awareness of” was coded the most at 13 times.

| People of Color | Prefer not to answer | White | Total | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDBE in the Workplace (IDBE) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4% |

| diversity hiring | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| token hire | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Negative behavior, experiences and/or attitudes (NBEA) | 8 | 1 | 11 | 20 | 36% |

| behavior_rude | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| colorism | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| confrontation | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| discrimination | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| IDBE hypocrisy | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| isolation | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| marginalization | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| microagression | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| obstacles to advancements | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| passing_worries | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| retention failure | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| internalize unawareness | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| unawareness_statement | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Positive behavior, experiences and/or attitudes (PBEA) | 3 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 16% |

| allies | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| camaraderie | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| ensure diversity | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| laudatory | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| mutual respect | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| witnessing IDBE | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | |

| Whiteness (W) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 9% |

| predominantly white workforce | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| white fragility | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| white privilege, awareness of | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| No Response (NR) | 4 | 1 | 14 | 19 | 35% |

| none | 4 | 1 | 14 | 19 | |

| TOTAL | 16 | 3 | 36 | 55 | 100% |

Of the five themes, IDBE appeared the least (two times) and was only mentioned by participants who identified as white. The subthemes that were mentioned were “diversity hiring” and “token hire.”

NBEA was coded the most at 20 times. Participants who identified as People of Color mentioned NBEA eight times, and participants who identified as white mentioned NBEA 11 times. There was one participant who did not self-describe and mentioned NBEA one time. Looking at the subthemes, participants who identified as white mentioned “behavior_rude,” “marginalization,” “passing_worries,” and “internalized unawareness.” Those from the category People of Color mentioned “colorism,” “isolation,” “obstacles to advancements,” and “retention failure.” Both groups mentioned “confrontation,” “discrimination,” “microaggression,” and “unawareness_statement.”

PBEA appeared nine times. Participants who identified as People of Color mentioned PBEA three times, and participants who identified as white mentioned PBEA six times. Looking at the subthemes, participants who identified as white mentioned “allies,” “ensure diversity,” and “witnessing IDBE.” Those from the category People of Color mentioned “camaraderie,” “laudatory,” and “mutual respect.” Both groups did not mention any overlapping subthemes.

W appeared five times. Participants who identified as People of Color mentioned W one time, those who identified as white mentioned W three times, and the participant who chose not to identify mentioned W one time. Looking at the subthemes, participants who identified as white mentioned “white privilege, awareness of.” Participants who identified as white and “prefer not to be identified” mentioned a “predominately white workforce.” Those from the category People of Color mentioned “white fragility.” People of Color and the other groups mentioned no overlapping subthemes.

After NR, the theme that was coded the most was NBEA at 20, slightly more than double the number of positive themes, PBEA at nine. Again, we observe with Q35 that most subthemes are in NBEA at 13 versus six for PBEA. This could allude to the possibility that STEMM librarians experienced many different forms of negativity rather than positivity in the workplace.

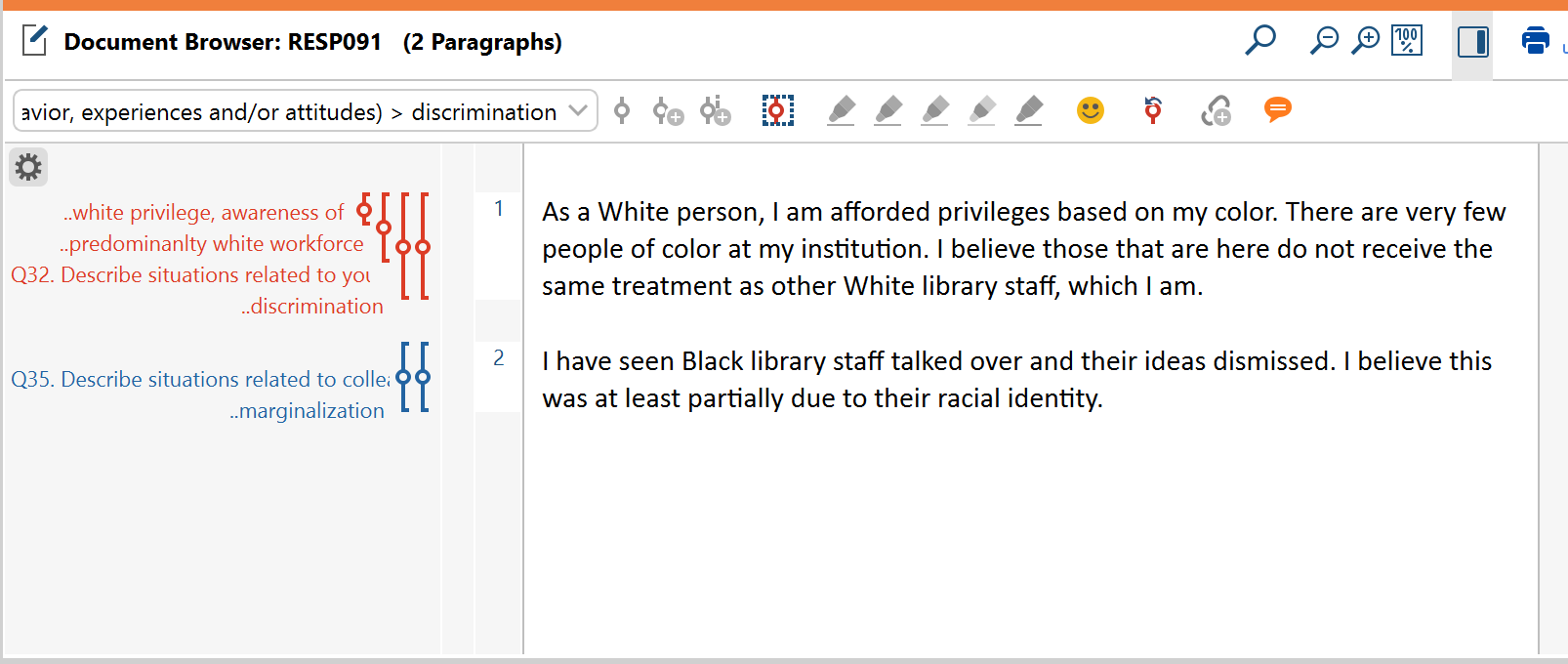

Experience Situations at Work Related to Racial/Ethnic Identity (Q32)

People of Color mentioned NBEA at about twice the rate of participants who self-identified as white. The question arises as to why this is the case. The participants of our study who are POC experience more negative behaviors, experiences and attitudes compared to the participants who identify as white, even though those who identify as white make up 69% of the participant population.

Across themes for Q32, the subthemes for both groups mainly differed except for two subthemes that both groups reported under the NBEA theme: “challenging colleagues of color” and “microaggression.” We self-define “challenging colleagues of color” as a “reference to being challenged by white colleagues because they are a Person of Color.” One POC participant stated, “Whites like to challenge the only African American on staff.” A participant who identifies as white commented, “Someone from outside (white, male, young, …) wasn't replying to the lead on a project, but emailing one of the other people on the project. The lead person is black, female, and tenured; the other person is white, female, and not yet tenured. I thought the outside person was acting in a racist way…” In both of these instances, library employees who are Black were challenged by colleagues (in the former) and someone from outside the library (in the latter). The quote from the POC participant is a statement reflecting on an ongoing common occurrence, while the white participant gave an account of something they witnessed and it made them uncomfortable.

Microaggression is “[e]veryday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative messages to target persons based solely upon their marginalized group membership.” One participant who is a POC stated, “One of our associate deans is very nasty to me and he never misses a chance to humiliate me at meetings and e-mail communications.” A participant who identifies as white commented, “I am a white person, and within the last month I believe I may have unknowingly used a micro-aggression phrase against a colleague (in a private setting). The person pointed out remembering the phrase, but with a laugh in their voice that I took to be nervous laughter. I've no idea how to approach the situation, but so far I've written a note letting them know how much I appreciate them (because I do). I haven't directly addressed the phrase yet, but I hope to start the conversation.” These are two accounts, one of a POC who is experiencing a microaggression and another of a white participant who unknowingly is the perpetrator.

There are not as many subthemes for PBEA as NBEA. However, both POC and white participants mentioned them an equal number of times, despite the considerable difference in the numbers of each group who participated in this survey. The subthemes “speak up for” and “equity” were mentioned by both groups. “Speak up for” is defined as “[expressing] one's opinion or one's support for someone or something.” On the theme “speak up for,” one POC participant noted, “Mostly having discussions with other colleagues around issues of race and the meaning of ethnic identity… Mostly, I seem to be challenging them on the issue of how others are perceived.” A white participant commented, “...especially when I speak in a group. If the same words were stated by a person of color, they likely would be assessed more carefully/critically.” Both participants are engaging in the labor of speaking up, though with the white participant, they realize that their words need not be assessed so much due to their privilege, while the Person of Color is actively engaging in the labor of social justice.

“Equity” is defined as the “[s]tate of affairs that is just, or fair…What equity means, how it is defined, and how it operates in practice vary considerably among organizations and individual educators.” For the theme “equity,” a participant who identified as white commented, “As a white woman in a medical library setting I am aware of my many privileges and actively take on learning opportunities around DEI in order to be better able to provide a more welcoming and equitable work environment for all.” A POC participant noted, “We produce exhibits to support EEO programs.” For both participants, there is the action of personal learning by participating in programs and educating others when constructing an exhibit.

The subtheme “camaraderie” is mentioned by POC participants and is defined as “a feeling of friendliness towards people that you work or share an experience with.” A POC participant noted, “We've started a group for the African-American librarians to gather just to talk about issues we're having, and it's been great to have that small group of support.” It is noted that perhaps camaraderie among other POC employees in the library is a source of strength, empowerment and feeling seen among minoritized employees.

Although both groups mentioned the theme “whiteness,” it was mentioned at an overwhelmingly increased rate among white participants compared to POC participants. The subtheme “white privilege, awareness of” is the most predominant subtheme among white participants. This is defined as “an awareness of unacknowledged and unearned advantages conferred on Caucasian people in the United States at the expense of people of color. White privilege benefits are socially, politically, and economically embedded at the systemic level and internalized at the psychological and interpersonal levels.” One participant replied, “As a White person, I am afforded privileges based on my color.” Another participant noted, “I mean, as a white woman, it seems like most work situations are made easier by my racial identity--everything is more or less set up in order to support my way of being in the world. It makes it hard to pinpoint a single thing.” This can be seen as a positive in that white STEMM librarians are recognizing the privilege they have and how this affects their lived experiences. It is also worth noting that the white participants were less likely to witness NBEA, according to our categories. That is, they are aware of their privilege but do not recognize negative instances of IDBE.

Still, when scrutinizing the data, there were a couple of instances where white participants in reporting their experience were actually narrating someone else’s personal experience. One white participant noted, “I have seen Black library staff talked over and their ideas dismissed. I believe this was at least partially due to their racial identity.” Another participant who identifies as white made the following comment, “I have seen people of color experience less respect at the desk for sure.” And yet another stated, “I must admit that I'm not the most observant person in the world. We did have one sad occurrence at a retreat about the future of libraries where the lone black male pointed out that he hoped the future of libraries would include more people that looked like him.” In our survey, we suspect there is a difference in how a white participant interprets the question versus how a POC interprets the questions. One way to explain this is that a white participant may think of this question as “I witnessed the experiencing of this,” whereas a POC might think of this question as “I experienced this.” We do not know where the participants are located geographically, as we did not ask this question on the survey. However, if the white participants are in the majority population where they work and/or live, the “witnessing” of egregious behavior may be the closest encounter to “experiencing.”

The subtheme, “whiteness and masculinity,” was coded six times, five by white participants and once by a POC. “Whiteness and masculinity” is defined as, “[T]o be White or male is to have greater access to rewards and valued resources simply because of one's group membership...[C]onsiderable privilege is conferred regardless of merit...Many White men today feel threatened because of what they perceive as attacks against White masculinity, and, for many, their racial identity is central to their identity as men.” One white male noted, “As an older white male, I don't even think my input on diversity issues holds any weight at all. The only thing I experience is a total lack of anything nice said about people like me in the workplace. We are unwanted dinosaurs who can't go extinct fast enough to please anyone.” Another white participant stated, “My institution is run exclusively by white people (men, of course), and I'm aware that I'm valued, in part, for also being white. I hate it and believe the institution suffers from its lack of diversity and failure to see its white/male power structure.” In this paper, we did not analyze our questions based on gender/gender identity, though because this has been coded for at a significant level, we wanted to bring this to the forefront.

Witnessing Situations Related to Racial/Ethnic Identity (Q35)

The theme IDBE was only reported by white participants, particularly “diversity hiring” and “token hire.” “Diversity hiring” is defined as “the development and implementation of a strategy that corrects for bias while attracting and retaining qualified candidates.” One response from a white participant that was coded as “diversity hiring” noted, “However, I was the chair of the search committee for hiring two new colleagues, and the whole library team is very excited that they are both women of color.” There is an emotional aspect of this case where there is genuine satisfaction in hiring qualified candidates who happen to be from minoritized populations. The definition of “token hire” is a “reference to a person who is an unqualified minority but is hired to provide appearance of racial diversity in the workplace.” A white participant whose response was coded for “token hire” commented, “A couple of diverse colleagues have very challenging skill sets and did not meet hiring guidelines but were nevertheless appointed at high levels to add diversity to staff.” In this case, the institution appears to be concentrating on the quantitative aspect of diversity, a point espoused by the book chapter “Leaning On Our Labor” in the book Knowledge Justice: Disrupting Library and Information Studies through Critical Race Theory, in which there is a challenge of how libraries are using Diversity Residencies to temporarily give the appearance of a much more diverse library than reality (Brown et al., 2021).

Regarding PBEA, there were no overlapping subthemes between white and POC participants. A closer look at the subthemes shows that similar subthemes between the two groups are “allies” by white participants and “camaraderie” by POC participants. We define “allies” as, “People who help and support people from another group and who unite with them for a common purpose.” A white participant stated that they would be “[a]ble to help someone with a foreign language.” “Camaraderie” is defined as “a feeling of friendliness towards people that you work or share an experience with.” A POC participant noted, “Users at the reference desk who are people of color appear to be particularly positive and engaged when they interact with a librarian who is a person of color.” With both terms, there is an underlying support and friendliness from helping those that share similar life experiences and those that don't share similar life experiences.

Limitations of This Study

As we mentioned, we analyzed Q2, Q32 and Q35 from our survey, and this alone does not give a complete picture of the climate that STEMM librarians are encountering when working. In the future, we intend to analyze more questions from this survey to reach a broader and more in-depth understanding of the climate of the lived experiences of STEMM librarians. However, even with only three questions, this survey provides an idea of the atmosphere STEMM librarians are encountering at work. It should also be noted that our survey was distributed on various listservs, none of which have any geographical boundaries. Therefore, we cannot make any assumptions that our participants are replying based on a North American view of IDBE. Nor are we in any position to give an indication that the results of this survey are in one or more geographical locations in the world. This study did not examine the intersectionality between gender and racial/ethnic identity; we would like to explore this in future data analysis. We mentioned that when a participant indicated one or more ethnicities or decided to self-describe, we added these individuals to the POC category to protect our participants' anonymity. However, it is hard to tell how each of these individuals appears in the world, especially for those individuals who indicated two or more ethnic/racial identities or who might be “passing.”

Conclusion

In this study, we have seen that POC participants experience negative behaviors, experiences and attitudes much higher than white participants, even though at least twice as many white librarians took part in the survey than POC librarians. The fact that there are far more subthemes for negative behavior experience and attitude for both questions reveal significant deficiencies in the climate of STEMM librarianship. We feel that negative outcomes can be changed in the name of social justice. Library leadership can set the tone for the climate in the library for its employees. Library leadership should take an active role in initiating policies and discussions that have a focus on IDBE and social justice, which are more than just superficial quantitative ones such as a committee or a collection, but also really listening to their staff and paying attention to issues in the larger scope of academia and society in general. Library leadership must provide tools that enable the sharing of emotional labor toward social justice in academic libraries. In addition, library leadership stands to gain valuable insights and advantages by collaborating with external organizations specialized in the advancement of social justice.

This study has also revealed that quite a few white participants are aware of their white privilege. None of the participants indicated in their responses that they use their white privilege to change the climate. Thus, the next step is putting the awareness into practice.

We believe that MLIS programs are a great place to start this education on the concepts of social justice and IDBE and how these can be applied to librarianship. The University of Rhode Island has a track for its Library Science Master's Degree program, Information Equity, Diverse Communities, and Critical Librarianship (MLIS Track, n.d.). University of California Los Angeles offers the following courses in its MLIS program, “Ethics, Diversity, and Change in the Information Professions,” “Critical Digital Media Literacies,” and “Environmental Justice through the Lens of Media and Education” (UCLA Registrar’s Office, n.d.). These are just a few examples of courses offered, and we hope these courses will become an embedded and essential component of MLIS curriculums.

If the results of this survey are an indication of the climate STEMM librarians are facing in academic libraries in general, there is a lot of work that still needs to be carried out to ensure that all STEMM librarians are experiencing more positivity and less negativity. As our study is the first study examining the lived experiences of STEMM librarians in academic libraries, we hope this has raised awareness about the climate STEMM librarians are encountering at work. Perhaps this awareness will lead individuals to take a stance and make a change in the name of social justice.

Acknowledgment

We thank Rebecca Orozco who was an original collaborator on this project and made contributions to the development of the survey and the analysis of the data. We thank Azure Stewart, PhD, who was instrumental in helping us navigate the qualitative research landscape. And we thank Matthew Frenkel for reviewing our paper.

References

Alabi, J. (2015). “This actually happened”: An analysis of librarians’ responses to a survey about racial microaggressions. Journal of Library Administration, 55(3), 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1034040

Anderson, A. J., DeLoach, M., Yeh, I., & Gomez, M. (1990). Jim Crow Jr. Library Journal, 115(12), 60.

Andrade, R., & Rivera, A. (2011). Developing a diversity-competent workforce: The UA Libraries’ experience. Journal of Library Administration, 51(7–8), 692–727. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2011.601271

Brissett, A., & Moronta, D. (Eds.). (2022). Practicing social justice in libraries. Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003167174

Brown, J., Cline, N., & Méndez-Brady, M. (2021). Leaning on our labor: Whiteness and hierarchies of power in LIS work. In S. Y. Leung & J. R. Lopez-Knight (Eds.), Knowledge justice: Disrupting library and information studies through critical race theory (pp. 95–110). MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11969.003.0007

Bugg, K. (2016). The perceptions of people of color in academic libraries concerning the relationship between retention and advancement as middle managers. Journal of Library Administration, 56(4), 428–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2015.1105076

Bussmann, J. D., Altamirano, I. M., Hansen, S., Johnson, N. E., & Keer, G. (2020a). Science librarianship and social justice: Part one: Foundational concepts. Issues in Science & Technology Librarianship, 94. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl62

Bussmann, J. D., Altamirano, I. M., Hansen, S., Johnson, N. E., & Keer, G. (2020b). Science librarianship and social justice: Part two: Intermediate concepts. Issues in Science & Technology Librarianship, 95. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl2570

Bussmann, J. D., Altamirano, I. M., Hansen, S., Johnson, N. E., & Keer, G. (2021). Science librarianship and social justice: part three: Advanced concepts. Issues in Science & Technology Librarianship, 97. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl2601

Bussmann, J. D., Altamirano, I. M., Hansen, S., Johnson, N. E., & Keer, G. (2022). Science librarianship and social justice: Part four: Capstone concepts. Issues in Science & Technology Librarianship, 100. https://doi.org/10.29173/istl2697

Caragher, K., & Bryant, T. (2023). Black and non-Black library workers’ perceptions of hiring, retention, and promotion racial equity practices. Journal of Library Administration, 63(2), 137–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2022.2159239

Chadley, O. A. (1992). Addressing cultural diversity in academic and research libraries. College & Research Libraries, 53(3), 206–214. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl_53_03_206

Chang, H.-F. (2013). Ethnic and racial diversity in academic and research libraries: Past, present, and future [Paper presentation]. Imagine, Innovate, Inspire: The Proceedings of the ACRL 2013 Conference, 182–193. American Library Association.

Charmaz, K. (Academic). (2017). An introduction to grounded theory [Video]. Sage Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473991798

Colón-Aguirre, M., & Cooke, N. A. (2022). LibCrit: Moving toward an ethical and equitable critical race theory approach to social justice in library and information science. Journal of Information Ethics, 31(2), 57–69.

Cooke, N. A., Sweeney, M. E., & Noble, S. U. (2016). Social justice as topic and tool: An attempt to transform an LIS curriculum and culture. The Library Quarterly, 86(1), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1086/684147

Ettarh, F. (2018). Vocational awe and librarianship: The lies we tell ourselves. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2018/vocational-awe/

Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction.

Gonzalez-Smith, I., & Swanson, J. (2014). Unpacking identity: Racial, ethnic, and professional identity and academic librarians of color. In N. Pagowsky & M. Rigby (Eds.), The librarian stereotype: Deconstructing perceptions of information work (pp. 149–173). Association of College and Research Libraries.

Hathcock, A. (2015). White librarianship in blackface: Diversity initiatives in LIS. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/lis-diversity/

Inclusion, diversity, belonging, equity, & accessibility (IDBEA). (n.d.). New York University. Retrieved February 17, 2023, from https://library.nyu.edu/about/general/values/idbea/

Information Studies (INF STD). (n.d.). University of California, Los Angeles. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://registrar.ucla.edu/academics/course-descriptions?search=INF+STD

Jaeger, P. T., & Franklin, R. E. (2007). The virtuous circle: Increasing diversity in LIS faculties to create more inclusive library services and outreach. Education Libraries, 30(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/10.26443/el.v30i1.233

Kim, K.-S., & Sin, S.-C. (2008). Increasing ethnic diversity in LIS: Strategies suggested by librarians of color. The Library Quarterly, 78(2), 153–177.

Leung, S. Y., & López-McKnight, J. R. (Eds.). (2021). Knowledge justice: Disrupting library and information studies through critical race theory. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11969.001.0001

Linares, R. H., & Cunningham, S. J. (2018). Small brown faces in large white spaces. In R. L. Chou & A. Pho (Eds.), Pushing the margins: Women of color and intersectionality in LIS (pp. 253–271). Library Juice Press.

Love, E. (2010). Generation next: Recruiting minority students to librarianship. Reference Services Review, 38(3), 482–492. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321011070955

MLIS Track: Information equity, diverse communities, and critical librarianship. (n.d.). University of Rhode Island. Retrieved March 18, 2023, from https://web.uri.edu/online/programs/graduate/master-of-library-and-information-studies/curriculum/mlis-track-information-equity-diverse-communities-and-critical-leadership/

Neely, T. Y., & Peterson, L. (2007). Achieving racial and ethnic diversity among academic and research librarians: The recruitment, retention, and advancement of librarians of color – A white paper. C&RL News, 68(9), 562–565. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.68.9.7869

Riley-Reid, T. (2017). Breaking down barriers: Making it easier for academic librarians of color to stay. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 43(5), 392–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.06.017

Rosa, K., & Henke, K. (2017). 2017 ALA demographic study. American Library Association. https://www.ala.org/tools/sites/ala.org.tools/files/content/Draft%20of%20Member%20Demographics%20Survey%2001-11-2017.pdf

Stanley, M. J. (2007). Case study: Where is the diversity? Focus groups on how students view the face of librarianship. Library Administration & Management, 21(2), 83–90. https://hdl.handle.net/1805/1440

Swanson, J., Tanaka, A., & Gonzalez-Smith, I. (2018). Lived experience of academic librarians of color. College & Research Libraries, 79(7), 876–894. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.7.876

Torres, A., & Magid, A. (2023). Lived experiences of STEMM librarians. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/M3VHQ

VERBI Software. (2022). MAXQDA 2022 [computer software]. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software. Retrieved from https://www.maxqda.com/

Vinopal, J. (2016). The quest for diversity in library staffing: From awareness to action. In the Library with The Lead Pipe. http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2016/quest-for-diversity/

Wheeler, M. B., & Hanson, J. (1995). Improving diversity: Recruiting students to the library profession. Journal of Library Administration, 21(3–4), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1300/J111V21N03_12

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License.